The Art of Making People Laugh

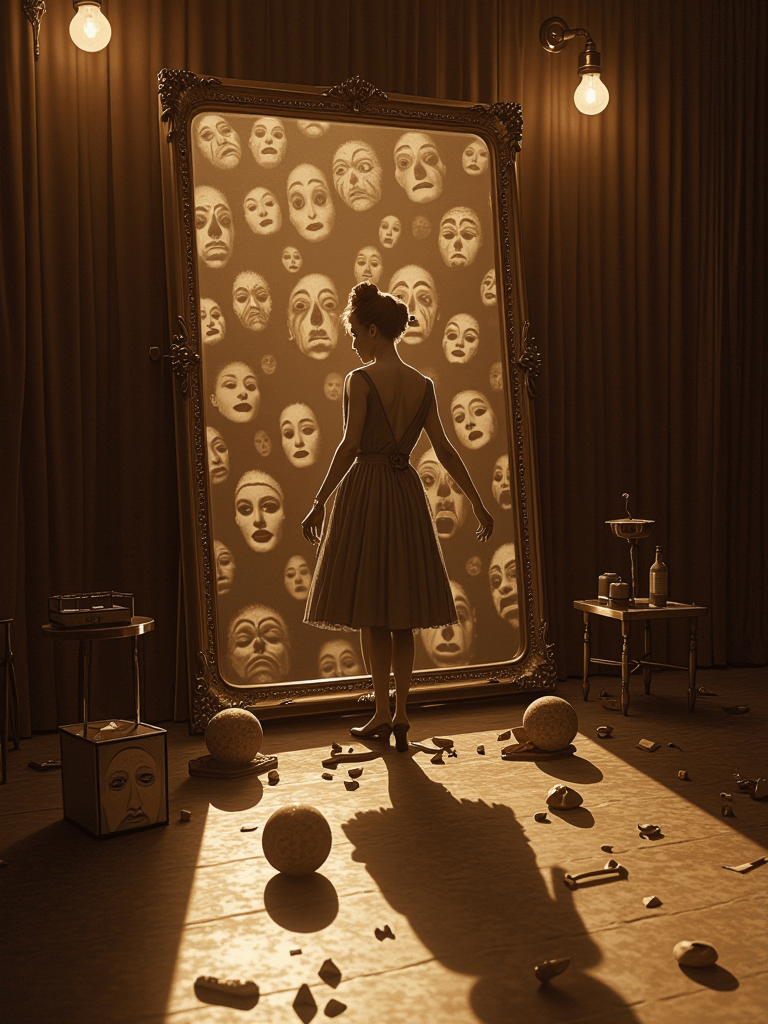

In the landscape of human expression, few art forms capture our collective psyche quite like sketch comedy. More than mere entertainment, it serves as a mirror—sometimes pristine, sometimes warped—reflecting back our societal quirks, cultural tensions, and shared absurdities. The evolution of sketch comedy charts not just the progression of performance styles or comedic techniques, but the shifting fault lines of what makes us uncomfortable, what binds us together, and what we’re willing to laugh about in public.

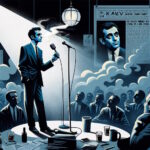

The Vaudeville Crucible: When Comedy Learned to Dance

The story begins in the smoky halls of vaudeville theaters, where comedy first learned to shed its literary pretensions and embrace the raw electricity of live performance. Here, in these proving grounds of American entertainment, performers discovered that humor could transcend the verbal—that a perfectly timed gesture or a well-choreographed bit of physical business could pierce through class divisions and language barriers alike. The vaudeville stage became an early laboratory for what would become sketch comedy’s core DNA: the ability to establish an entire world, populate it with instantly recognizable characters, and then systematically dismantle it, all within the span of minutes.

What distinguished the vaudeville approach from mere slapstick was its sophisticated understanding of audience psychology. Performers like Weber and Fields weren’t just executing practiced routines; they were conducting real-time experiments in group dynamics, learning precisely how long to hold a pause, when to subvert an expectation, and—perhaps most crucially—how to make failure itself entertaining. This last innovation would prove particularly influential, establishing a tradition of meta-comedy that continues to resonate through contemporary sketch work.

The Radio Revolution: When Comedy Learned to Whisper

The transition from vaudeville’s broad gestures to radio’s intimate whispers forced sketch comedy to evolve in ways that would permanently alter its genetic makeup. Without the safety net of visual performance, writers and performers had to construct entire worlds through sound alone—a limitation that paradoxically expanded comedy’s experimental frontage. Shows like “It Pays to Be Ignorant” and “The Jack Benny Program” discovered that audience imagination could be a more powerful tool than any physical prop or set piece. The medium’s constraints gave birth to what might be called comedy’s “negative space”—the art of implying rather than showing, of letting silence and suggestion do the heavy lifting that previously required elaborate stagecraft.

This era also witnessed the emergence of what we might now recognize as modern comedy writing rooms. The pressure to produce regular content for weekly broadcasts necessitated a kind of collaborative creativity that would have been alien to vaudeville performers. Writers learned to think in terms of structure rather than just individual jokes, developing sophisticated approaches to callback humor and running gags that could sustain themselves across entire seasons. The result was a new understanding of comedy as architecture rather than just performance—a crucial shift that would influence everything that followed.

Television’s Golden Age: When Comedy Learned to See Itself

The arrival of television might have seemed like a simple return to visual comedy, but the medium’s particular attributes—its unprecedented intimacy, its ability to reach millions simultaneously, its demand for weekly content—created something entirely new. The sketch comedy that emerged in the 1950s and evolved through the 1960s represented a unique hybrid: it combined radio’s sophisticated writing structures with vaudeville’s physical comedy while adding television’s ability to break the fourth wall through direct address and meta-commentary.

Shows like “Your Show of Shows” with Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca demonstrated that sketch comedy could achieve a kind of complexity previously reserved for theatrical productions, while still maintaining the immediate accessibility required for broad appeal. The format began to develop its own internal language: the cold open, the callback, the escalating absurdity, the third-act twist. Perhaps most significantly, television sketch comedy discovered it could comment on itself—could make the very act of producing television content part of the joke. This self-referential tendency, first explored as a novelty, would eventually become one of the format’s defining characteristics, reaching its full flowering in later programs like “Saturday Night Live” and “SCTV.”

The Digital Disruption: When Comedy Learned to Fragment

The arrival of digital platforms didn’t just add new distribution channels for sketch comedy—it fundamentally reorganized the art form’s relationship with time, attention, and cultural context. Where television had demanded rigid time slots and broadcast standards, digital platforms introduced a kind of quantum mechanics to comedy: sketches could be any length, reach any audience, and exist in multiple contexts simultaneously. This liberation from traditional constraints produced both innovation and chaos, as creators grappled with an environment where the boundaries between professional and amateur, viral and forgotten, brilliant and disposable became increasingly porous.

What emerged was a new comedy ecosystem characterized by its molecular structure rather than its institutional framework. Groups like The Lonely Island and later CollgeHumor demonstrated how digital sketches could function as self-contained units of cultural DNA, replicating and mutating as they spread across platforms. The format adapted to exploit the particular psychology of online viewing—the brief attention spans, the hunger for shareable content, the desire for insider recognition. Yet paradoxically, this fragmentation enabled new forms of complexity. Sketches could now build on shared cultural references with unprecedented specificity, assuming levels of audience knowledge that would have been impossible in the mass-market era.

The contemporary sketch landscape reveals itself as a kind of quantum superposition of its entire evolutionary history. In any given moment, you might find traces of vaudeville’s physical comedy on TikTok, radio’s sophisticated sound design in podcasts, television’s self-referential complexity on YouTube, all transformed by digital culture’s peculiar alchemy. The result is not so much a progression as a proliferation—an explosion of possibilities that suggests sketch comedy’s essential role as a tool for processing and reconstructing our shared reality has only grown more vital in the digital age.

This democratization of creation has revealed something fundamental about sketch comedy’s nature: its power lies not in production values or traditional expertise, but in its ability to crystallize moments of shared recognition—to take the nebulous feelings and unspoken observations floating through our collective consciousness and give them sharp, memorable form. In this sense, the digital revolution hasn’t changed sketch comedy’s essential function so much as stripped it down to its core: the ancient, vital practice of using structured play to make sense of an increasingly complex world.

The Ever-Evolving Punchline: Sketch Comedy’s Continuing Metamorphosis

Looking back across sketch comedy’s evolutionary landscape reveals something profound about human consciousness itself: our persistent need to disassemble and reconstruct reality through the lens of play. What began in vaudeville’s crucible as a way to bridge cultural divides has evolved into something more essential—a distributed system for processing collective experience, a cultural debugging tool that helps us identify and resolve the glitches in our shared operating system.

The format’s resilience speaks to its fundamental alignment with how human minds process complexity. Like dreams, sketches provide a space where logical contradictions can peacefully coexist, where emotional truths can override physical laws, where the absurd and the obvious can reveal themselves as two sides of the same coin. This psychological utility explains why sketch comedy has not only survived but thrived through each technological disruption—it’s not just entertainment, but a form of collective sense-making that becomes more vital as our shared reality grows more complex.

As we look toward the horizon, the emergence of artificial intelligence and virtual reality suggests yet another transformation on the horizon. These technologies promise (or threaten) to blur the boundaries between creator and audience, between performance and reality, in ways that early vaudeville performers could scarcely have imagined. Yet the core dynamic remains unchanged: humans gathering, virtually or physically, to metabolize their experiences through structured play, to transform their anxieties into laughter, to make the incomprehensible digestible through the ancient alchemy of comedy.

What sketch comedy’s evolution reveals, ultimately, is not just the development of an art form, but the outline of a fundamental human need—the need to step outside our reality just far enough to see its seams, its absurdities, and its possibilities. In this light, every new platform, every technological shift, every cultural revolution becomes not a threat to the format but an opportunity for it to demonstrate its remarkable adaptability, its essential role in helping us navigate the ever-increasing complexity of human experience. The punchline, it seems, is that we need comedy not despite our sophistication, but because of it.