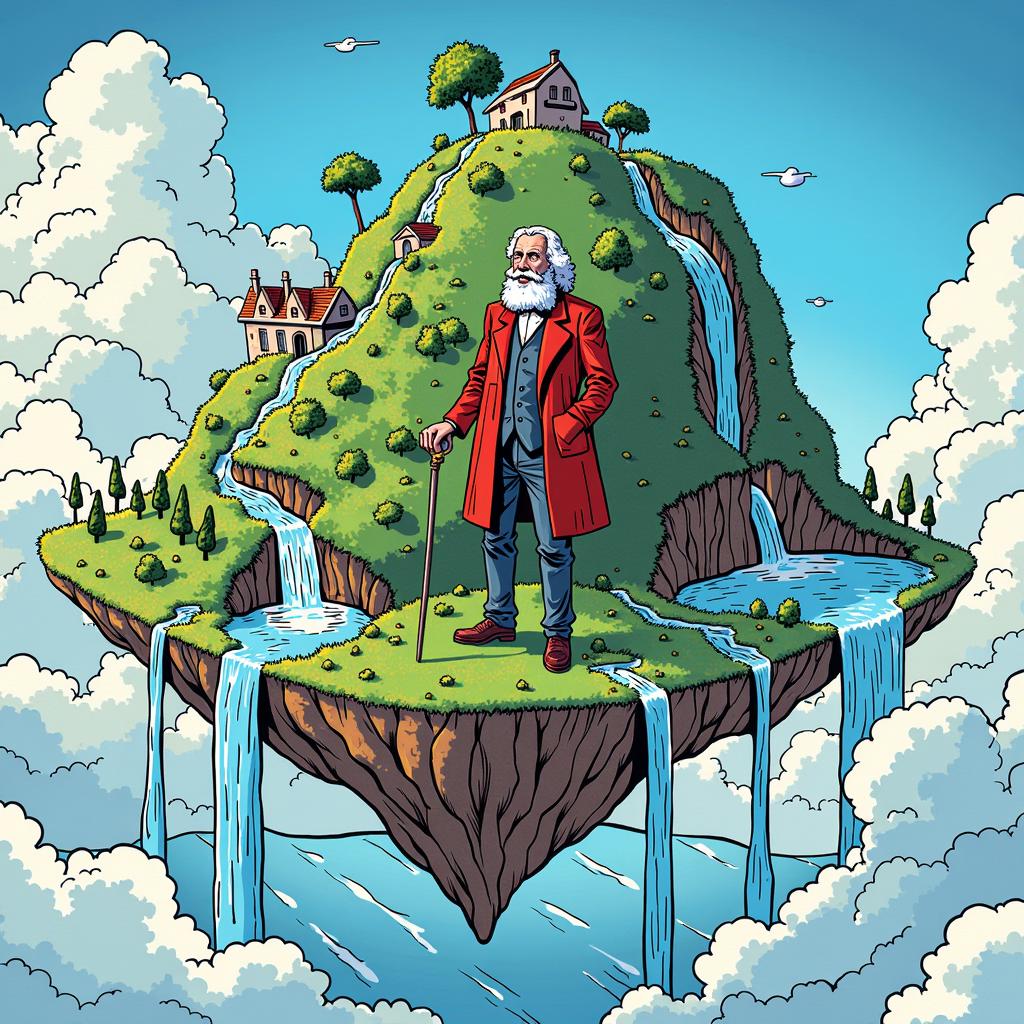

Darwin’s World

In the verdant expanse of the Galapagos Islands, where the sun dips into the horizon and paints the sky with hues of crimson and gold, a man once stood at the precipice of discovery. Charles Darwin, the stalwart traveler, naturalist, and philosopher, embarked on a journey that would forever alter the fabric of our understanding of the world.

As we wander through the pages of his autobiography, “The Voyage of the Beagle,” we find ourselves entwined in the intricate dance of observation, curiosity, and introspection. The young Darwin, barely 23 years old at the time, set sail on a voyage that would span nearly five years, crossing vast expanses of ocean and traversing uncharted territories.

It was during this journey that the seeds of his most famous theory were sown. The encounters with the finches, tortoises, and other creatures of the Galapagos sparked an epiphany within him – a realization that the diversity of life on Earth was not a product of divine design, but rather a consequence of natural selection.

As Darwin navigated the complex web of causality, he found himself grappling with questions that had haunted philosophers for centuries. What is the nature of existence? How do we define the boundaries between creator and creation? The more he delved into the mysteries of evolution, the more he became aware of the provisional nature of his own understanding.

“I am like a boy who has stumbled upon a still-unfathomed secret in his school-days,” Darwin wrote to his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker. “It is so strange that I can hardly believe it myself.”

This humility before the unknown was a hallmark of Darwin’s philosophical approach. He recognized that the pursuit of knowledge was not a triumph of human understanding, but rather an acknowledgment of its limits.

In the midst of this intellectual ferment, Darwin also found himself grappling with the complexities of morality and faith. His own Christian upbringing had instilled in him a sense of awe and reverence for the natural world, yet his growing awareness of evolution’s impact on traditional notions of creation left him with more questions than answers.

“I have sometimes thought it a great pity that there should be any natural beings which we cannot explain,” he mused. “But, my dear Mr. Gray, I am convinced that this is rather an advantage in the long run.”

This paradox – between the need for explanation and the acceptance of the unknowable – underscores Darwin’s philosophical stance on the nature of truth. For him, understanding was not a binary proposition, where one could claim absolute certainty or dogmatic conviction.

Rather, he sought to cultivate a sense of ambiguity, an openness to the complexity and nuance of reality. This was reflected in his famous dictum: “It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the most adaptable to change.”

In this regard, Darwin can be seen as a philosopher who embodied the Aristotelian ideal of “the mean.” He recognized that human understanding must oscillate between extremes – between dogmatic certainty and radical uncertainty. It is through embracing this middle ground that we may begin to grasp the intricate web of causality that underlies our existence.

As we reflect on Darwin’s legacy, it becomes apparent that his work represents a synthesis of two seemingly disparate philosophical traditions: empiricism and transcendentalism. The former – emphasizing observation, experimentation, and the accumulation of evidence – laid the groundwork for modern scientific inquiry.

The latter – positing the inherent meaning and purpose in human existence – provided a counterpoint to the mechanistic worldview that Darwin sought to challenge. His synthesis, as it were, reconciled these two

perspectives, revealing the intricate dance between observation and interpretation.

In conclusion, Charles Darwin’s world remains an enigmatic realm of wonder, where philosophical inquiry converges with scientific exploration. As we navigate the twists and turns of his thought-provoking narrative, we find ourselves confronting the fundamental questions that have long plagued human existence: What is our place in the natural world? How do we define the boundaries between creator and creation?

It is through an introspective examination of these questions – through a willingness to confront the unknown and the unknowable – that we may come to understand the true depth of Darwin’s philosophical vision. One that not only acknowledges the provisional nature of our understanding, but also invites us to embark on a journey of discovery, guided by the quiet confidence that “the greatest good for the greatest number” lies not in dogmatic certainty, but in the uncertain yet profound beauty of existence itself.